Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 55, No.1 - Spring 2009

Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas.

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 55, No.1 - Spring 2009 Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas. |

INTRODUCTION TO PHOTOGRAPHER ANDREW

MIKSYS

Andrew Miksys, BAXT. Vilnius: Arok, 2007

Cameos of the Roma: Miksys Confronts the Gypsy Persona

K. PAUL ŽYGAS

K. Paul Žygas teaches architectural history at the Institute of Design and the Fine Arts, Arizona State University. He is currently researching the works of Italian architects in Vilnius.

Some 3,000 Roma, or gypsies, reside in Lithuania today, most of them in Vilnius, the rest scattered about in Eišiškės, Seredžius, Žargarė, Troškūnai, and Pajuodupis. Andrew Miksys visited these towns and villages from 1999 to 2006, selecting forty-nine color photographs from his encounters for the album at hand.The title BAXT, printed boldly in gilt on the black cloth cover, is not an enigmatic acronym, but an ordinary Romani word, pronounced “bacht,” which, depending on the context, can mean luck, fate, destiny, fortune, karma, or kismet. It is an altogether apt choice for the book’s title because the assembled images suggest that neither the Roma nor their relationship to the society enveloping them is likely to change anytime soon.

The Roma people arrived on Europe’s southern shores sometime in the thirteenth century. The beachhead slowly fanned out, small groups from the larger diaspora reaching the Grand Duchy of Lithuania around 1500. Relations between Roma and the host populations tended to be rocky from the very start. The old problems, still unresolved, made headlines recently when Italian lawmakers aired their grievances last year in the European parliament. The Lithuanians, too, have their share of the usual complaints, but the extent to which they may or might not be valid is not the intent of this review to address.

The Roma taboras in the southern outskirts of Vilnius is a small neighborhood located near the end of the #1 bus line. It is a grey no-man’s land which the townspeople prefer to avoid. Situated next to railroad tracks and nearby an abandoned industrial site, the grounds remain neglected today. Hard-packed oily dirt serves the derelict area as its paths and streets. A few trees, scraggly bushes, and unkempt grass cling to life as best they can. The houses are small, one-story high wooden structures of dubious legal and structural status.

Miksys somehow managed to win the Roma’s trust, which gained him entry into their homes. It is an achievement in itself as their private realm is generally off-limits to outsiders. He even attended a wedding or two, in all likelihood attended by just about everyone in the clan. He could observe and portray the entire community, but the snapshots of a few old men excepted, those of adult males and women, infants and toddlers are entirely missing from BAXT. Instead, Miksys used the strategy of conveying information about the whole by concentrating on just one of its parts. Focused almost entirely on teen-agers and adolescents, BAXT presents a condensed and intense, but wholly dispassionate, portrayal of Roma youth living in Lithuania today. What holds true for this particular subset, presumably, also holds true for the rest, including those members of the society who were not actually shown.

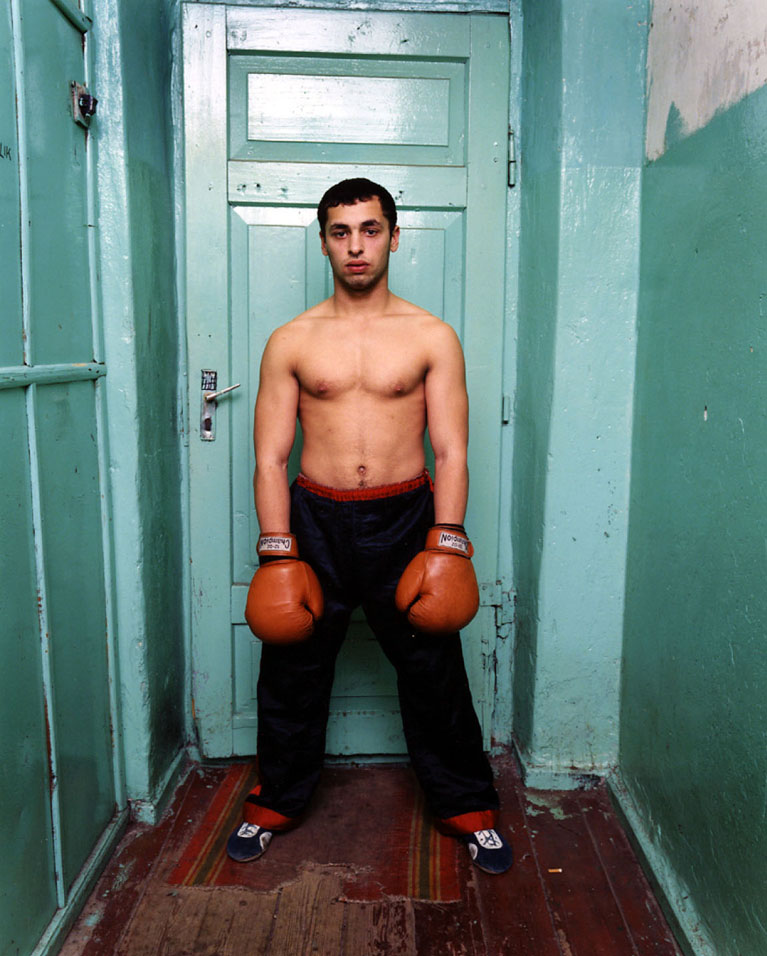

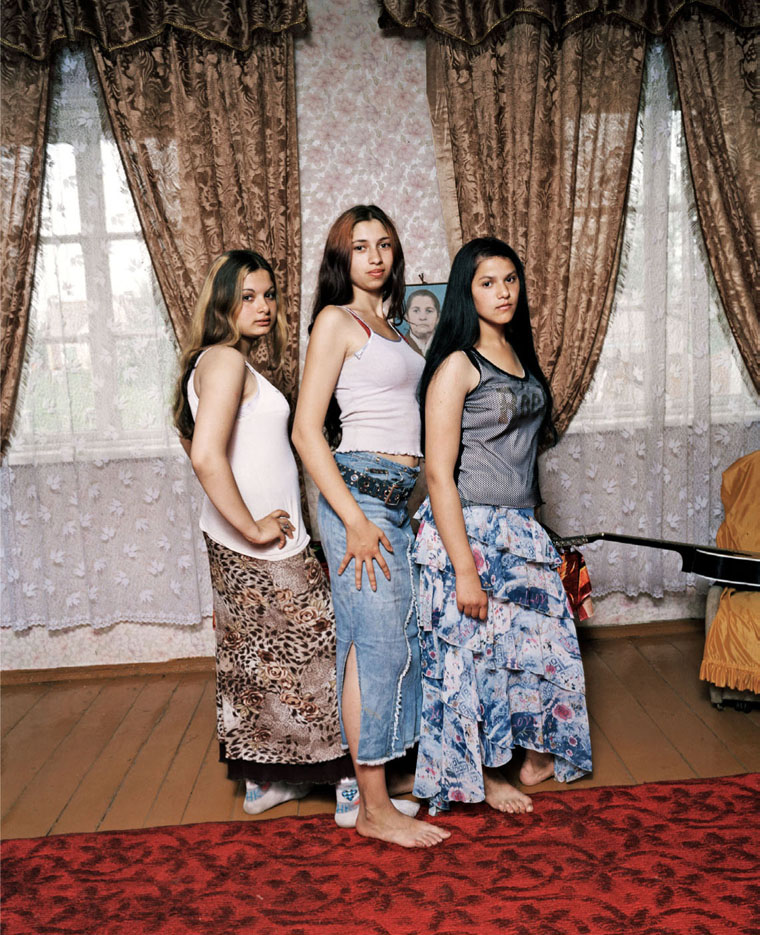

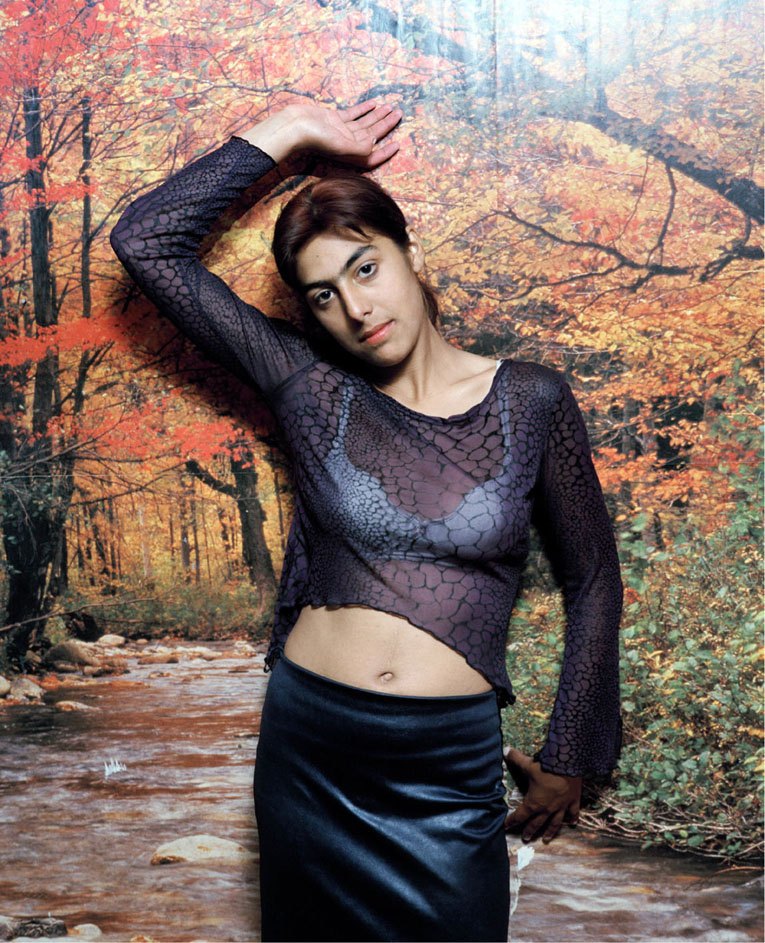

The portrayed faces betray little, if anything, resembling personal self-satisfaction or general contentment. Even Miksys’ most junior subjects confronted the camera without smiles. Throughout the entire album we are confronted by dead-pan, expressionless gazes. The portraits of the young Roma toughs clearly state that they are a hard lot, their clenched fists expressing “attitude” with plenty of spunk to spare for anyone trespassing their turf. The young women, defiantly independent, flaunt their very personal and unconventional views about fashion, combining stuff in ways never seen in teen style magazines. The youngest Roma girls are probably responsible for the hearts and heart motif images which pop up in the most unexpected places – as little boxes, sofa cushions, cutouts on radios, chalked on the walls, and as studded patterns on the imitation leather covering the insulation of padded doors. Pretty lace curtains, favorite plastic mementoes, and cute fuzzy things suggest that sometimes their flights of fancy transcend the conspicuously shabby surroundings.

A few photos provide glimpses into interiors holding some up-scale sectional furniture and up-to-date electronics. Even so, the rooms seem altogether forlorn, as if they had been neglected for years, nonchalantly left alone to the passage of time and to the action of the elements. Miksys did not sanitize the physical context. Never judgmental, he did not divert his lens from the exposed wiring, tacked linoleum, peeling wallpaper, cracking and mildewed plaster. The result: a visual record of contemporary Roma life that is as ruthlessly frank as it is historically suggestive.

Miksys’ revelatory shots become most evocative once we realize that the Roma do not share Western assumptions about the good life. To appreciate BAXT we must enter the Romani mind-set and to accept it on its own particular terms. The album suggests that the Roma have changed little, if at all, from the time of their arrival on European shores. Confronting the society in which they found themselves with disbelief, they have stayed suspicious and skeptical about it ever since. Ever ignoring the norms and conventions of Western society, to this very day the Roma have remained its perennial, congenital, and archetypal outsiders. Miksys’ portraits make it clear that the gypsy people do not share our aspirations or anxieties. Holding true to their old and ingrained habits of thought and behavior, they disdain official societal organization, side-stepping most of the usual responsibilities and benefits, such as full-time employment, insurance plans, family summer vacations, consumer-class creature comforts, time-schedules, retirement plans, and credit cards.

To the best of my knowledge, the Roma provide services but do not produce any marketable goods. They take, as if by right, the surplus produced by the society surrounding them; nevertheless, they are not particularly keen on amassing possessions. It is besides the point to say that their interiors seem forlorn, that their unkempt community seems impermanent. They do not wish it to be otherwise. It would be out of character for the Roma to live in homes with showcase interiors and manicured lawns. They do not treasure material belongings nor the rooted life. As a result, it is difficult to find the proper expression for the semi-permanent Vilnius taboras. It is less than a rooted settlement, but somewhat more than a transient encampment. Certainly here today, but it may very well turn out to be evanescent and gone tomorrow.

Andrei Codrescu’s introductory essay is a gem, a deftly-written sketch concentrating on and illuminating the lingering effects of Soviet rule. He points out that Roma life abounds with ironies and stubborn incongruities. Codrescu explains that pride in traditional Romani ways provided partial immunity from the enveloping socialist contagions, helping the community to survive with its identity intact. Although the Roma endured many decades of communist rule, they seem reluctant to shake off, to abandon, the mementoes of the regime’s material detritus. The Roma were among the first in the Soviet Union to have access to Western goods, but neither did they succumb to, much less capitulate, to the materialist West. Codrescu lauds Miksys for finding and capturing the bedrock humanity in his subjects, an assessment that readers of BAXT will surely share.

This album project was funded in part by grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the J. William Fulbright Program, and the Lithuanian Department of National Minorities. In 2002 the Photo District News named Andrew Miksys as one of the “top 30 emerging artists to watch,” and in 2006 Slate magazine featured him as the “Artist of the Month.” Born in Seattle, he now divides his time between the US and Vilnius.

Superman Boy, Vilnius, 1999.

Robert and Liuba (Groom and Bride),

Eišiškės, 2001.

Rustan and Apple Trees, Pajuodupis, 2000.

Kostas (Boxer), Vilnius, 2004.

Young Couple (Budulay with Girlfriend), Vilnius, 1999.

Misha and Boris, Vilnius, 2005.

Roza, Zala, Tamara, Eišiškės, 2004.

Zarina, Vilnius, 2001.

Spartak, Pajuodupis, 2006.

Grigor “The Boss” and Stalin,

Eišiškės, 2004.